But DES or 3DES are the most likely suspects.

→ Other 64-bit block ciphers, such as IDEA, were once common, and the ineptitude we are about to reveal certainly doesn’t rule out a home-made cipher of Adobe’s own devising. That, in turn, suggests that we’re looking at DES, or its more resilient modern derivative, Triple DES, usually abbreviated to 3DES. With all data lengths a multiple of eight, we’re almost certainly looking at a block cipher that works eight bytes (64 bits) at a time. Stream ciphers are commonly used in network protocols so you can encrypt one byte at a time, without having to keep padding your input length to a multiple of a fixed number of bytes. We can rule out a stream cipher such as RC4 or Salsa-20, where encrypted strings are the same length as the plaintext. The next question is, “What encryption algorithm?”

Adobe database leak password#

The password data certainly looks pseudorandom, as though it has been scrambled in some way, and since Adobe officially said it was encrypted, not hashed, we shall now take that claim at face value. Remember that hashes produce a fixed amount of output, regardless of how long the input is, so a table of the password data lengths strongly suggests that they aren’t hashed: The first question is, “Was Adobe telling the truth, after all, calling the passwords encrypted and not hashed?”

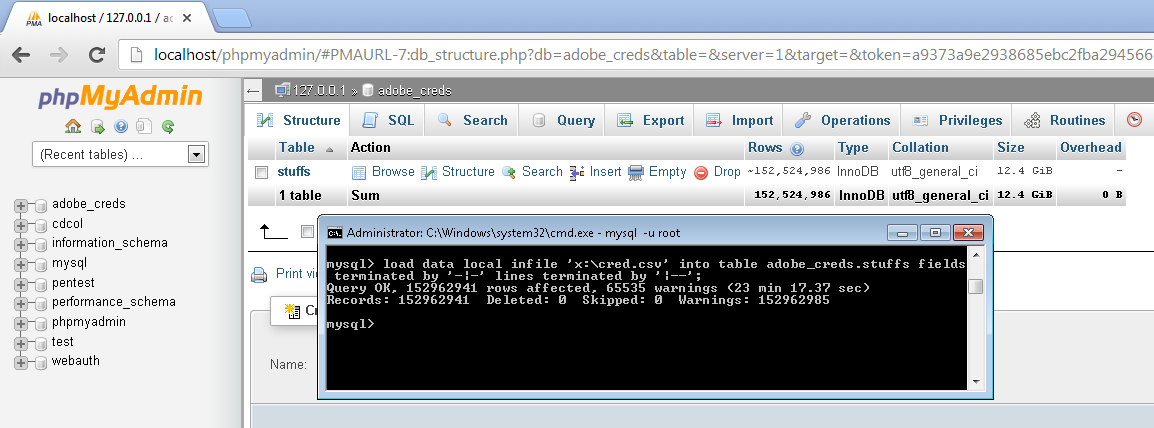

We kept the password hints, because they were very handy indeed, and converted the password data from base64 encoding to straight hexadecimal, making the length of each entry more obvious, like this: The user IDs, the email addresses and the usernames were unnecessary for our purpose, so we ignored them, simplifying the data as shown below. We think this provided a representative sample without requiring us to fetch all 150 million records.īy inspection, the fields are as follows:įewer than one in 10,000 of the entries have a username – those that do are almost exclusively limited to accounts at and (a web analytics company). We took every tenth record from the first 300MB of the comressed dump until we reached 1,000,000 records. → Our sample wasn’t selected strictly randomly. We used a sample of 1,000,000 items from the published dump to help you understand just how much more. It seems we got it all wrong, in more than one way.Ī huge dump of the offending customer database was recently published online, weighing in at 4GB compressed, or just a shade under 10GB uncompressed, listing not just 38,000,000 breached records, but 150,000,000 of them.Īs breaches go, you may very well see this one in the book of Guinness World Records next year, which would make it astonishing enough on its own. Even if two users choose the same password, their salts will be different, so they'll end up with different hashes, which makes things much harder for an attacker. you also usually add some salt: a random string that you store with the user's ID and mix into the password when you compute the hash. This means that you never actually store the password at all, encrypted or not. Today's norms for password storage use a one-way mathematical function called a hash that uniquely depends on the password.

He passwords probably weren't encrypted, which would imply that Adobe could decrypt them and thus learn what password you had chosen. One of our complaints was that Adobe said that it had lost encrypted passwords, when we thought the company ought to have said that it had lost hashed and salted passwords. We took Adobe to task for a lack of clarity in its breach notification. One month ago today, we wrote about Adobe’s giant data breach.Īs far as anyone knew, including Adobe, it affected about 3,000,000 customer records, which made it sound pretty bad right from the start.īut worse was to come, as recent updates to the story bumped the number of affected customers to a whopping 38,000,000.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)